Understanding Probabilities, Odds and Log-Odds

Introduction

Probabilities, Odds, and Log-Odds play an important role in social science and data science. In this post, let’s explore simple ways to understand them.

You can find codes in R and in Python at the end of this post.

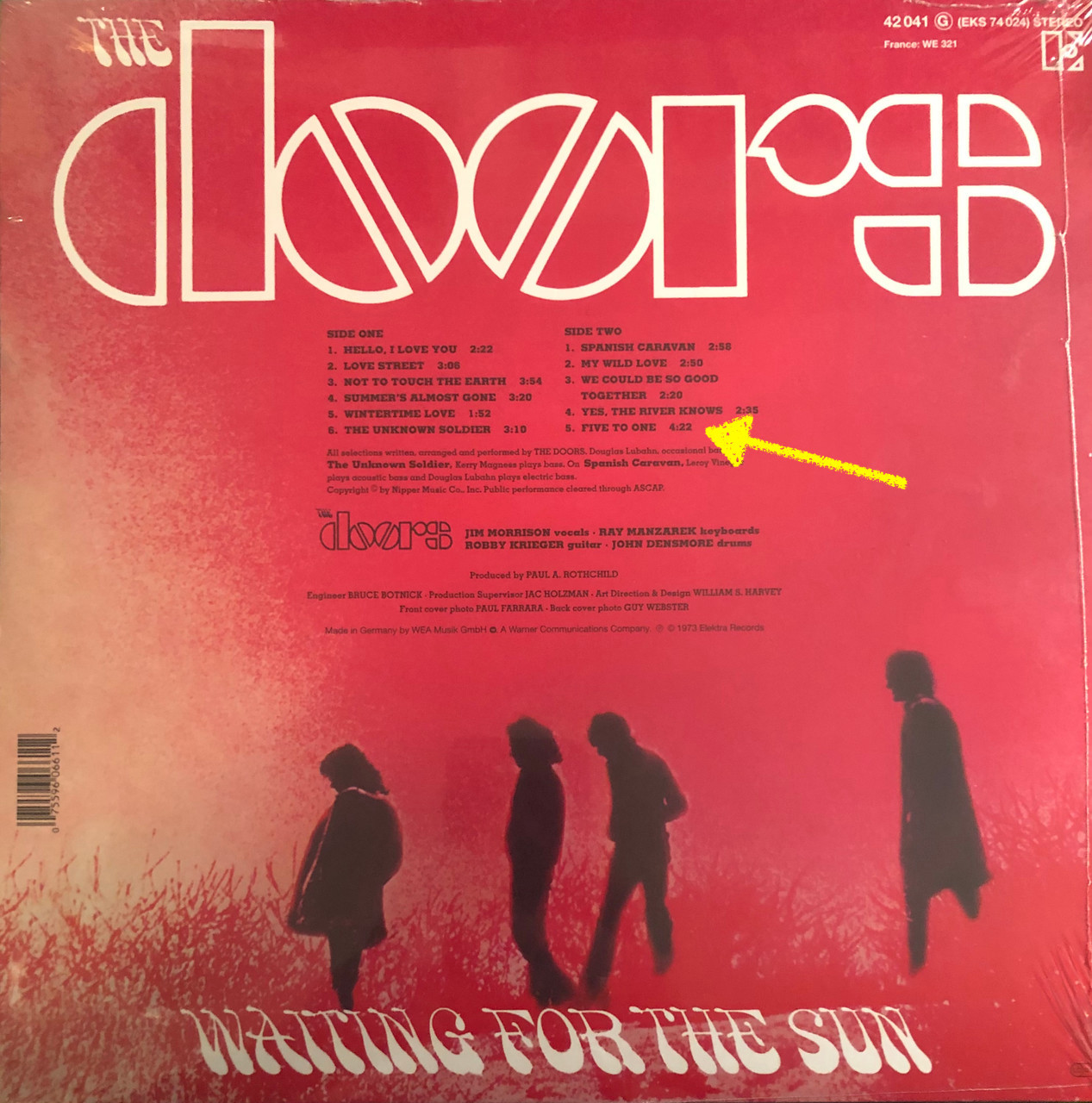

In the third album of the Doors, Waiting for the Sun, there is an amazing song called “Five to One”.

Five to One or \(5:1\) is an odds.

Odds and Probabilities

Before talking about odds, let’s build some foundations.

An odds or a probability is often invoked in the context of the “success” of an “event”. Let’s call the event \(X\) and define success as \(X = 1\). A classic example is basketball free throws. Success in this case is straightforward: scoring.

You can also conceive \(X = 1\) more generally such as getting a job, getting into a car accident, etc. This will depends on the context of your question.

Let’s focus here on binary event, i.e. events that can only be either “success” or “failure”, \(1\) or \(0\).

Before going into odds, let’s start with the concept of probability, which I believe is more intuitive.

A probability of success is simply the probability of the outcome of interest divided by the total numbers of attempts / trials.

If in general you score 60 free throws out of 100 attempts (or trials), then your probability of success is \(\frac{80}{100} = 0.8\).

This is simply

\begin{equation} P(X=1) = \frac{\text{number of success}}{\text{number of trials}} \end{equation}

We generally use the symbol \(\pi\) (pi) to denotes the probability \(P(X=1)\).

The probability of success is

\begin{equation} \pi \end{equation}

The probability of failure is

\begin{equation} 1 - \pi \end{equation}

The probability of successful free throws in the NBA is 0.8 (or 80%). A simple (Frequentist) interpretation is that when we calculate the probability success of many many throws in the NBA (e.g. 1 million throws) we get 80% of successful attempts. Some players or some teams have higher probabilities and some players have much lower probabilities.

The idea of odds is close to the idea of probability. Instead of dividing the number success by the total number of trials, we divide the number of success by the number of “failure” or non-success.

The odds is defined by

\begin{equation} \text{odds} = \frac{\pi}{1-\pi} = \frac{\text{success}}{\text{failure}} \end{equation}

Again if you shoot 100 throws, score 80 and fail 20 you have the odds \(80:20\)

\begin{equation} \frac{80}{20} = \frac{0.8}{0.2} = 4 \end{equation}

Here are some probabilities and odds based on 100 trials (success on the left and failure on the right for the odds).

\[\begin{aligned}[ht] \begin{array}{rrlr} \hline & \text{pr} & \text{odds} & \text{odds} \\ \hline 1 & 0.000 & 0:100 & 0.000 \\ 2 & 0.050 & 5:95 & 0.053 \\ 3 & 0.100 & 10:90 & 0.111 \\ 4 & 0.250 & 25:75 & 0.333 \\ 5 & 0.500 & 50:50 & 1.000 \\ 6 & 0.800 & 80:20 & 4.000 \\ 7 & 0.900 & 90:10 & 9.000 \\ 8 & 0.990 & 99:1 & 99.000 \\ \hline \end{array} \end{aligned}\]Let’s create functions to retrieve odds and retrieve probabilities in R

# for a 83% probability, we get the odds of

f_odds = function(p) p / (1-p)

f_odds(p = 0.83334) # 5

# for an odds of 5, we get the probability of

f_proba = function(odds) odds / (1 + odds)

f_proba(odds = 5)

\begin{equation} \text{odds} = \frac{\pi}{1-\pi} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \pi = \frac{\text{odds}}{1+\text{odds}} \end{equation}

Log of Odds

Taking the natural logarithm of the odds is a common transformation. The main reason is the mathematical properties of this transformation. It is just more convenient to work with the log of the odds rather than the odds.

\begin{equation} \text{log-odds} = \ln \left(\frac{\pi}{1-\pi}\right) \end{equation}

Note the property

\begin{equation} \ln \left(\frac{\pi}{1-\pi}\right) = \ln(\pi) - \ln(1-\pi) \end{equation}

# example

log(0.2/0.8) == log(0.2) - log(0.8)

The distribution created by the log of odds is symmetrical and centered at 0, when the probability is 0.5, which is a \(50:50\) odds. However, the log cannot deal with the number of 0 or 1.

\[\begin{aligned}[ht] \begin{array}{rrlrr} \hline & \text{pr} & \text{odds} & \text{odds} & \text{log odds} \\ \hline 1 & 0.00 & 0:100 & 0.00 & - \infty \\ 2 & 0.01 & 1:99 & 0.01 & -4.60 \\ 3 & 0.05 & 5:95 & 0.05 & -2.94 \\ 4 & 0.10 & 10:90 & 0.11 & -2.20 \\ 5 & 0.25 & 25:75 & 0.33 & -1.10 \\ 6 & 0.50 & 50:50 & 1.00 & 0.00 \\ 7 & 0.80 & 80:20 & 4.00 & 1.39 \\ 8 & 0.90 & 90:10 & 9.00 & 2.20 \\ 9 & 0.99 & 99:1 & 99.00 & 4.60 \\ \hline \end{array} \end{aligned}\]To illustrate further let’s create a plot showing the mapping of probabilities into log-odds.

Let’s create a probability distribution, from 0.01 to 0.99. Then let’s use our R function to take the odds, and then let’s take the log of the odds.

proba = seq(0.01, 0.99, by = 0.01)

odds = f_odds(proba)

log_odds = log(odds)

Let’s plot

plot(proba, log_odds)

Log-odds are also known as the logit function.

From Log-Odds back to Probabilities

Remember that the inverse operation of taking the natural logarithm is the exponential.

For instance the log of \(10\) is \(2.302585\), and the exponential of \(2.302585\) is \(10\).

\begin{equation} \text{exp}(\ln(10)) = 10 \end{equation}

In R

log(10) # = 2.302585

exp(2.302585) # = 10

exp(log(10)) # = 10

Therefore, if we have a log-odds scale, which is formally written \(\ln(\text{odds})\), then by taking the exponential, we retrieve the odds.

For instance, if we have the log-odds value of 1.386, and we take the exponential of 1.386, we get approximately 4, which was the result of our 80 successful throws and 20 failed throws.

\begin{equation} \text{log-odds} = \ln \left( \frac{\pi}{1-\pi} \right) \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \text{exp}(\text{log-odds}) = \frac{\pi}{1-\pi} = \text{odds} \end{equation}

Finally we can go back to probabilities (\(\pi\)) with the following equations.

From odds

\begin{equation} \frac{\text{odds}}{1 + \text{odds}} = \pi \end{equation}

From log-odds

\begin{equation} \frac{\text{exp}(\text{log-odds})}{1 + \text{exp}(\text{log-odds})} = \pi \end{equation}

another way to write this equation is

\begin{equation} \frac{1}{1+\text{exp}(- \text{log-odds})} = \pi \end{equation}

In our example of the odds of \(80:20\), odds of \(4\), or 80% probability of success of free-throws, we have

\begin{equation} \frac{80}{20} = 4 \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \ln(4) = 1.386294 \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac{\text{exp}(1.386294)}{1 + \text{exp}(1.386294)} = 0.8 = \pi \end{equation}

Note that in R you have the ready-made function plogis which retrieve probabilities from log-odds

plogis(1.386) # 0.8

Formal names

\begin{equation} \gamma = \text{ln} \left( \frac{p}{1-p} \right), \rightarrow \text{logit transformation} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} p = \frac{1}{1 + \text{exp}^{-\gamma} } = \frac{\text{exp}(\gamma)}{\text{exp}(\gamma) + 1}, \rightarrow \text{logistic transformation} \end{equation}

Functions in R and Python

R

# pi to odds

f_proba_to_odds = function(p) p / (1-p)

# odds to pi

f_proba_from_odds = function(odds) odds / (1+odds)

# pi to log-odds

f_proba_to_log_odds = function(p){

log_odds = log(p / (1-p))

return(log_odds)

}

# log-odds to pi

f_log_odds_to_proba = function(log_odds){

p = exp(log_odds) / (1 + exp(log_odds))

return(p)

}

f_proba_to_odds(p = 0.8) # = 4

f_proba_from_odds(odds = 4) # = 0.8

f_proba_to_log_odds(p = 0.8) # = 1.386

f_log_odds_to_proba(log_odds = 1.386294) # = 4

Python

import math

def f_proba_to_odds(p):

odds = p / (1 - p)

odds = round(odds, 3)

print(odds)

def f_proba_from_odds(odds):

p = odds / (1+odds)

p = round(p, 3)

print(p)

def f_proba_to_log_odds(p):

log_odds = math.log(p / (1-p))

log_odds = round(log_odds, 3)

print(log_odds)

def f_log_odds_to_proba(log_odds):

p = math.exp(log_odds) / (1 + math.exp(log_odds))

p = round(p, 3)

print(p)

f_proba_to_odds(p=0.8)

f_proba_from_odds(odds=4)

f_proba_to_log_odds(p=0.8)

f_log_odds_to_proba(log_odds=1.386)

Exercises

- Convert the probability \(p=0.25\) into a log-odds

- Retrieve the probability from a log-odds of \(0.1\)

- Retrieve the probability from an odds of \(3\)